September 6 – December 17, 2011 —

The Massachusetts Historical Society holds a considerable collection of Francis Parkman ephemera, including journals detailing his travels on the Oregon Trail (which evolved into a series for the monthly magazine Knickerbocker, and later a book) and various notes and correspondence relating to later books. Also in the collection are items of a more personal nature, including gardening records and correspondence with his father. This exhibition focuses on selections from Parkman’s collection of Native American images – specifically in carte de visite form. Carte de visite refers to a small, collectable trading card. Many of the images in this exhibition were taken by Omaha photographers. They document not only some of the Native Americans who traveled through Omaha, but also record the pioneer spirit of traveling photographers, and the visuals create a valuable historical reference.

Cartes de visite gained popularity following the rise in the collectability of calling cards in the 1850s. Calling cards, engraved with a visitor’s name, were presented to a host upon arrival. Historical records indicate that occasionally an intrepid photographer would experiment with a portrait card that could be used to take the place of the traditional calling card. However, examples are rare, and vary in size and by photographic process. Photographer André Adolphe Disdéri of Paris patented a process for creating 2.5 x 4 inch portrait cards, which would become the standard size for portrait and scenic cards to come. This particular size of card became what we acknowledge as the carte de visite. Napoleon III has erroneously been credited with inciting an extraordinary demand for pocket-sized portraiture. A charming, but untrue, tale describes Napoleon’s stop at Disdéri’s studio during his march to Italy, so that his image could be converted to cartes de visite for friends and fans. Napoleon did indeed pose for cartes de visite, but it is unlikely that he was responsible for the trend that would gain tremendous popularity in Europe and the Untied States.

Though photographers developed varying methods to create multiple images (Disderi’s process utilized a camera with four lenses, and resulted in eight negatives on an 8 x 10 glass plate), the cards were usually made from a thin albumen photo print adhered to cardboard for stability. The process was cost-effective, making cartes de visite affordable for the masses. People were finally able to afford portraits to share with friends and loved ones. The petite size of the cards lent itself to easy mailing and collectability. In the United States, where the carte de visite debuted in late summer of 1859, the Civil War became the impetus for the widespread collecting of the cards. Soldiers posed for portraits before departing for battle – their loved ones reciprocated, and everyone received a sustaining photographic memento. These remembrances could be kept in albums specifically designed for that purpose. “Card portraits, as everybody knows, have become the social currency, the ‘green-backs’ of civilization,” stated Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1863. Even Queen Victoria was affected by the craze. Her album contained over 100 cartes de visite of acquaintances. Despite their immense popularity, cartes de visite were but a brief phenomena. They were replaced by cabinet cards in the 1860s, which allowed for larger format images.

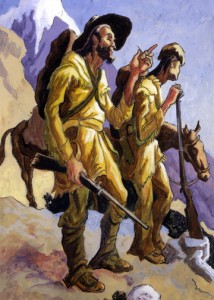

Francis Parkman was greatly interested in the Native Americans, as evidenced in The Oregon Trail, and by extensive writings collected by the Massachusetts Historical Society. It’s no surprise that two of his carte de visite albums are dedicated to their images. It is an interesting coincidence, however, that a number of the images displayed in this exhibition were produced by studios with connections to William Henry Jackson, one of several artists who illustrated a reprint of The Oregon Trail in 1931.