View artwork

Frank A. Rinehart was born in Lodi, Illinois in 1862. In 1878, he and his brother Alfred moved to Denver, Colorado and soon found employment with the photography studio of Charles Bohm. During this time, he possibly worked for the railroad as a photographer. In 1881 the Rinehart brothers began working with William Henry Jackson, a photographer who had achieved fame for his majestic landscape images of the West. Under Jackson’s tutelage, Frank perfected his photography skills and developed an interest in Native American culture.

On September 5, 1885, Frank Rinehart married Anna Ransom Johnson (daughter of Willard Bemis Johnson and Phebe Jane Carpenter) in Denver County, Colorado. Frank and Anna moved to Omaha, Nebraska where they had two daughters, Ruth and Helen. In 1885 Rinehart opened a photography studio in the Brandeis Building located at 210 South 16th Street in downtown Omaha. In 1898 Omaha staged the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, providing Rinehart an opportunity of a lifetime.

Businessmen in Omaha raised nearly $1 million in 1895 to get the Exposition started. It was patterned after the great Chicago World Fair, The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. Like Chicago’s, the architecture in Omaha was made from plaster of Paris and reinforced with corrugated metal. Eleven major buildings and several smaller ones were constructed to house displays from 40 states and 10 foreign countries. The grounds covered 184 acres transformed by 5,000 workers in what would be today’s near north side of Omaha. They created a large court – all in various period styles of architecture surrounding a Venetian-style lagoon.

From June 1, 1898 through November 1, 1898, Omaha became the site of the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition highlighting the achievements of the developed West from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Coast. A historically significant part of the Exposition was the Indian Congress conceived by the editor of the Omaha Bee, Ed Rosewater. He wanted to show the cultural diversity of the Native American life style by bringing together 35 (some sources list 34, others 36) different tribes and over 500 Native Americans, the largest gathering of its kind. At this time, Native Americans were viewed as a people of a vanishing way of life. They were seen as noble and not as an enemy to be feared – an image furthered during the Exposition. The Indian Congress was managed by Captain W. A. Mercer of the 8th U. S. Infantry, under the direction of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs acting on behalf of the country’s Secretary of the Interior. The Indian Congress occurred during the last three months of the Exposition, beginning August 4 and ended November 1, 1898.

It is the purpose of the promoters of the proposed encampment or congress to make an extensive exhibit illustrative of the mode of life, native industries, and ethnic traits of as many of the aboriginal American tribes as possible. To that end it is proposed to bring together selected families or groups from all the principal tribes and camp them in tepees, wigwams, hogans, etc., on the exposition grounds, and permit them to conduct their domestic affairs as they do at home, and make and sell their wares for their own profit.

(“The Indian Congress of 1898: About the Indian Congress of 1898” Omaha Public Library website, 1998)

Some of the tribes represented were the Apache, Arapaho, Assiniboine, Blackfoot, Calispel, Cheyenne, Chippewa, Crow, Flathead, Iowa, Kiowa, Kootenai, Omaha, Otoe, Ponca, Pueblo, Sauk, Sioux, Tonkawa, Winnebago, and Wichita. The largest contingent was the Sioux and included Chief Red Cloud, now nearly 80 and blind. Large groups of Sioux traveled from the nearby South Dakota reservations – Rosebud, Crow Creek, Cheyenne River, Lower Brule, Pine Ridge, and Standing Rock. Geronimo, the famous Apache warrior, was also there, held under constant guard by U.S. soldiers.

Frank Rinehart was selected as the exclusive official photographer for the Exposition and the only photographer allowed on the Indian Congress grounds. He was provided a studio in one of the smaller Exposition buildings, located at the northeast corner of the Grand Court. His duties were to photograph the physical structures, events of the fair, visiting dignitaries, and later the Native Americans invited to the Indian Congress.

Because of the tremendous amount of work this generated, Rinehart hired Adolph Muhr as his assistant. Muhr was the older of the two, having been born in about 1858 in New York City. Muhr’s family had moved to Hoboken, New Jersey in the 1870s. It is possible that Adolph learned photography there by working in a local studio. In 1883 he moved to Denver and opened a studio on the corner of 16th and Larimer with a William L. Bates. After the Exposition, in 1903 he went on to manage a studio for Edward S. Curtis, another noted photographer.

Rinehart and Muhr began photographing Native American representatives at the Congress in their studio, using an 8 x 10″ glass-negative camera with a German-made lens. They created platinum prints to achieve the broad range of tonal values afforded by that medium. The two photographed more than 500 delegates to the Indian Congress, including the great Chiefs Geronimo, Red Cloud, and White Swan. Muhr was primarily responsible for the photographs that the Rinehart Studio made during the Indian Congress.

The archives of the Burke Museum of Natural Museum and Culture at the University of Washington have a small catalogue, entitled Rinehart’s Platinum Prints of American Indians and printed in 1899. In it, Muhr wrote an introduction that provides a unique insight into his experience of photographing the Native Americans.

Being employed by Mr. Rinehart, the official photographer, the writer was assigned the task of photographing the Indians, into which he carried the zest of a novel experience. They were timid at first, hung back like children, but a little coaxing and a better acquaintance soon made for smooth sailing. (copied sheet, MONA artist file)

John Carter, in his article for NEBRASKAland Magazine, writes, “[Muhr] unlike other photographers before him, was deeply concerned about the pictorial qualities of his photographs. He was not content with simply recording what people looked like; rather, he made images that were strong portraits of individuals. He attempted to capture some of the spirit of the people.” (October 1987, p. 40)

Tom Southall, former photograph curator at the University of Kansas’ Spencer Museum of Art, said of its collection of Rinehart’s work at the Indian Congress: “The dramatic beauty of these portraits is especially impressive as a departure from earlier, less sensitive photographs of Native Americans. Instead of being detached, ethnographic records, the Rinehart photographs are portraits of individuals with an emphasis on strength of expression. While Rinehart and Muhr were not the first photographers to portray Indian subjects with such dignity, this large body of work which was widely seen and distributed may have had an important influence in changing subsequent portrayals of Native Americans.” (Haskell Indian Nations University F.A. Rinehart Gallery website)

Simon J. Ortiz writes in Beyond the Reach of Time and Change: “The actual significance of that body of work is its representation of that historical era in which the Indian is portrayed as the Vanishing American – that is ‘the Vanishing Red Man,’ ‘The Vanishing Indian’ – principally meaning the disappearance of the Vanquished Indigenous Peoples and cultures of the Americas.” (Ortiz, p. 4)

However he goes on that this is not true of the Rinehart/Muhr photographs. The story told by those images is one of the triumphs of the white man over the red man, the U.S. over the Indian Nations.

Rinehart was originally to work with the Smithsonian Institution and provide them a study collection of Native American images. However, Muhr’s images became so popular that Rinehart broke his contract with the Smithsonian, copyrighting the pictures and selling them for a profit. Argument over picture copyrights eventually led to Muhr leaving Rinehart’s employ.

During the Exposition, Rinehart published Rinehart’s Indians, a book with 46 fine half-tone reproductions printed on both sides and two-color plates bound in an illuminated paper cover that sold for 50 cents. Another version was printed only on one side of heavier paper and had four-color illustrations for $1.00. His platinum prints were commonly 7 x 9″ and sold for $1 each or $10 per dozen unmounted. A mounted and color print cost $3. Around thirty of the best images were 14 x 17″ on platinum paper, unmounted, and sold for $3 each. For $7 you could have them in color. He also sold other sizes and styles.

The portraits of the Native American representatives brought Rinehart fame and success. During 1899 and 1900, Rinehart and Muhr traveled to various reservations, photographing Native American leaders who had been unable to attend the Congress, as well as capturing images of everyday indigenous life and culture. Rinehart took more than 1,200 portraits during those two years. The Indian images taken at this time are rarer than those taken at the Indian Congress. Some of these photographs were made into paintings and others into lithographs available for sale.

Frank Rinehart created an extraordinary legacy of images. He died on December 17, 1928, in New Haven, Connecticut. His widow, Anna Rinehart continued to operate the business with her son-in-law George Marsden until ill health forced her to retire in 1952. Marsden also produced a unique album of portraits using 65 of the negatives. He bound 16 x 20” prints in a split leather album with artwork burnished into the front and back covers. A flyleaf was included to identify each image by name and tribe as well as a brief biography. He later produced a second album using 65 different images. Marsden operated the Rinehart studio until his own death in 1966.

Currently, the largest collection of Rinehart’s photographs of Native Americans is preserved at Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, Kansas. Funded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Hallmark Foundation, the collection has been organized, preserved, copied, and cataloged. Because of this project that started in 1994, the works are now cataloged in a computer database mostly available online. The database includes images from both Omaha’s 1898 Exposition and the subsequent 1899 Greater America Exposition, studio portraits from 1900, and photographs by Rinehart taken at the Crow Agency in Montana, also in 1900. The Library of Congress also holds more than 60 of Rinehart’s portraits of Arapaho, Assiniboine, Blackfeet, Fox, Kiowa, Pueblo, Sac, Sioux, and Tonkawa tribal delegates. The Omaha Public Library collection, which it received as a donation in 1951, includes over 500 photographs of Native Americans taken by Rinehart. Many of these photographs are portraits of individuals, as well as group photos of families and various every-day activities.

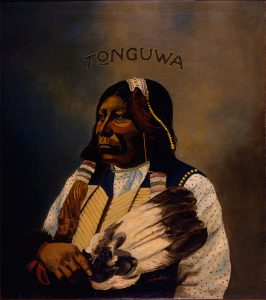

Following are some of the captions for various images:

Poor Dog, Sioux. Poor Dog was among the 88 members of the Sioux tribe. The Sioux were appreciated for their spectacular dress and in particular, the feathered bonnets worn for parades and other ceremonies. (Peterson)

Chief American Horse, Ogalalla Sioux. One of the greatest Indian orators. He has headed innumerable delegations of his people to confer with the authorities at Washington. (Rinehart)

John Hollow Horn Bear, Cheyenne River Sioux. Son of the Chief of the Cheyenne River Sioux,. He has been educated, but is slow in adopting the ways of civilization. (Rinehart)

Swift Dog, Standing Rock Sioux. With his shield and war club he looks like a Roman gladiator. (Rinehart)

Chief Little Wound, Ogalalla Sioux. Friend and lieutenant of Chief Red Cloud, he aided in many of the troubles in which that crafty leader involved his people. (Rinehart)

Turning Eagle, Lower Brule Sioux. An old warrior and a very jolly fellow (one of the few pictures where subject is smiling). (Rinehart)

(Spellings are those used by the authors.)

Sources:

- Beyond the Reach of Time and Change: Native American Reflections on the Frank A. Rinehart Photograph Collection, by Simon J. Ortiz. University of Arizona Press (April 28, 2005)

- The Face of Courage: The Indian Photographs of Frank A. Rinehart, by F. A. Rinehart. Introduction: Royal Sutton. Old Army Press. Ft. Collins, Colorado. 1972.

- Native American Portraits 1862-1918: Portraits from the Collection of Kurt Koegler , by Nancy Hathaway. Chronicle Books, San Francisco. 1990

- Images of America: Omaha’s Trans-Mississippi Exposition, by Jess R. Peterson. Arcadia Publishing. 2003

- Rinehart’s Indians, published by Frank Rinehart. Omaha, Nebraska. 1899.

“Image Makers”, by John Carter. NEBRASKAland Magazine. Vol. 65, No. 8, October 1987. Published by Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Lincoln, NE. pp34- 41

Web Pages:

- “American Treasures of the Library of Congress” http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/trm233.html

- Wikipedia – Indian Congress 1898 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_Congress

- Frank A. Rinehart http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Rinehart

- Frank A. Rinehart Collection at the Haskell Indian Nations University Cultural Center

& Museumhttp://www.haskell.edu/cultural/pgs/_rinehart.html - “The Indian Congress of 1898: About the Indian Congress of 1898” Omaha Public Library website, 1998 http://digital.omahapubliclibrary.org/transmiss/congress/about.html

Additional Sources:

- The Dusty Shelf, Vol. 17, No. 2, 1998, “Frank Rinehart’s Legacy of Images: A Centennial Rememberance,” Bobbi Rahder.

- http://www.umkc.edu/kcaa/DUSTYSHELF/DS17-2.htm#Frank Rinehart’s Legacy of Images

Researched and compiled by James M. May, 2009, a project of MONA’s Bison Society.