View artwork

Born April 15, 1889 and growing up in Neosho, Missouri only several decades after the Civil War, Thomas Hart Benton remembered many stories of Union and Confederate veterans and the old settlers from the hills of the Ozarks. These characters made for colorful tales in the isolated little town.

Politicians were significant in young Benton’s life. He was named for his legendary grand-uncle, a Democratic senator when Missouri entered the Union. The politics played out by Benton’s father, a lawyer and congressman, gave Benton an intense concern for the American land and its destiny. From early childhood, he traveled with his father on political tours, observing the country. These early experiences deeply rooted in him a respect for rural and small town people, only to resurface at a later time and come into full bloom with the art of the Regionalists.

According to his father, the only occupation for a Benton son was that of a lawyer, as only responsible and intelligent men entered the field, and it naturally led to political power. Understandably the elder Benton could not appreciate his son’s penchant for drawing. In his autobiography, An Artist in America, Benton recounts, “I had drawn pictures all my life. It was a habit and Dad’s disapproval didn’t affect me in the least. I didn’t think of being an artist. I just drew because I liked to do so.”

And draw he did. Benton’s artistic career began early in his youth as a cartoonist for a Joplin, Missouri newspaper. The following year, he enrolled at The Art Institute of Chicago where the exposure to great artists broadened his perception of the art world. This inspired him to pursue his training in the art capital of the world at the time. Paris, Benton said, put young men in highly romantic and emotional states of mind.

Disillusioned, as so many artists before him, with the tedious task of copying from casts and following the formulas laid down by the Paris schools, Benton gave them up to work independently in his studio. Unable to formulate any particular style, he experimented with many of the Parisian modernisms, and particularly the colorist theory of Synchromism in which the formula was simply form derived from the play of color.

With World War I looming, Benton returned to America, settling in New York City. Fresh with knowledge of the classics and familiar with the new conventions, it took one more step for Benton to realize the direction his art ultimately would take him. Circumstances of World War I provided this step.

In line for the draft and not wanting, as Benton confessed, to interfere with the progress of any German bullets, he enlisted in the navy. In 1918 he was assigned to the new naval base in Norfolk, Virginia, where he worked as a draftsman, making drawings of the base as records for the architects. For Benton there was a distinguishable contrast in the affected people of the New York and Paris art worlds and the young men on the base from the hinterlands of America. In the latter, he found a common ground, a return to his rural values. Benton could not deny the lure of his own family’s history and, as an artist, sought a style that conveyed these emotions.

When he returned to New York, Benton had enough self-confidence and cockiness to scorn the pretentious art community and to pursue a representative art that would be of his own and of his country. At this time, he began his summer treks to a little Massachusetts island – a summer ritual that was carried on for more than 50 years. In Benton’s words, “It was in Martha’s Vineyard that I first really began my intimate study of the American environment and its people.”

The time was right for Benton. His life experiences, his art training, and the renewed interest in the American tradition after the War by the creative community allowed Benton to develop as an artist.

In 1922 Benton married Rita Peacenza, a talented, beautiful Italian with a flair for the dramatic. She handled all aspects of his life which allowed him the time to develop and work as an artist. They had met when she was a student in an evening art class that Benton was teaching at a neighborhood public school. Their son Thomas was born in 1926 and daughter Jessie in 1939.

“ … Rita mentioned to Robert Henri, a very influential force in the New York art world at the time, whom she met through Tom, that she was taking art lessons from Benton. ‘What do you think of his work?’ she remembered asking him. ‘Oh, he’s too Michelangelese,’ Henri replied, and dismissed the subject. But it didn’t affect her interest in her teacher or the lessons …”

Sometimes controversial, always vocal, Benton gained a reputation as one of America’s foremost painters. Even though critics and peers were harsh, newspapers and magazines throughout the world reproduced and published his work.

In 1935 Benton turned his back on the eastern art establishment, moved permanently to Missouri, and continued to cultivate his grass roots style of art called Regionalism. He became an instructor of drawing and painting at the Kansas City Art Institute where his most famous pupil was the Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock; his well known Nebraska students were Aaron Pyle and Bill Hammon. Regionalism reached its height of popularity in the 1930s with Benton as its chief proponent. The triumvirate of Grant Wood from Iowa, Kansan John Steuart Curry, and Benton rose from the heartland to tell the story of middle America. Benton recalled,

“Actually the three of us were pretty well educated, pretty widely read, had European training, knew what was occurring in modern French art circles, and were tied in one way or another to the main traditions of Western painting. What distinguished us from so many other American painters of our time was not a difference in training or aesthetic background but a desire to redirect what we had found in the art of Europe toward an art specifically representative of America.”

Although the movement was short-lived, the country was now conscious of its rich diversity of customs and people.

Thomas Hart Benton can be considered a visual historian. In his long and turbulent art career, he had witnessed vast changes and growth in the land and its people. Yet he recorded and preserved the rural scene all across America. He painted what he saw, as it was, without an idyllic cover. He died January 19, 1975 in his Kansas City studio.

Thomas Hart Benton provided the world with a visual legacy which earned him an important position in the history of American art. As a writer, he left numerous essays and several autobiographies. An Artist in America is personal, full of his wonderful wit and sarcasm; An American in Art surveys his growth professionally and technically. To read these books is to see the struggle, the influence, and the growth to maturity which is reflected in his style, the style which makes him stand above others, where the world takes notice and pays homage.

The Oregon Trail by Francis Parkman

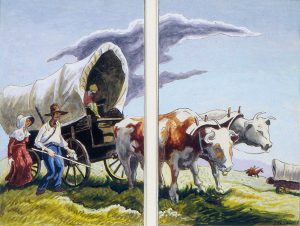

Francis Parkman, author of The Oregon Trail, a proper Bostonian and an 1844 Harvard graduate, promptly pursued his interest in history regarding Indians and the wilderness by traveling west to the Rocky Mountains. He began his journey at St. Louis, first going to Fort Laramie via the Platte River through Nebraska, to Bent’s Fort in Colorado and then back to the river town where he started. From this overland journey, he wrote of the large herds of buffalo, the Indians who hunted them, and his experiences observing this drama. The Oregon Trail was first published in 1847 and 100 years later Thomas Hart Benton took Parkman’s word pictures and turned them into 28 artworks.

Both Thomas Hart Benton and Francis Parkman had an inherent love for the land and waterways of their homeland. When Benton traveled the back roads and rural areas of the country, he filled his sketch books with material for his paintings. Historian Parkman also went to the American wilderness, filled his diaries with research material, and wrote extensively on the native and foreign inhabitants of North America.

Benton made only a short reference in his autobiography to his work as an illustrator of books. “During this time I also illustrated a number of books, but these also dealt mostly with happenings of the past.” In actuality, he was a renowned book illustrator, doing books for a variety of authors from H.L. Mencken to John Steinbeck.

Through the years, The Oregon Trail was illustrated by a variety of artists. First serialized in The Knickerbocker magazine in 1847-1849, later book-length editions of The Oregon Trailfeatured illustrations by renowned artists. Frederic Remington provided over six dozen black-and-white sketches for the 1892 edition. These were replaced by the color paintings of N.C. Wyeth in 1925 and William H. Jackson in 1931. In 1943, color paintings and line drawings by Maynard Dixon illustrated the text. Thomas Hart Benton’s watercolors accompanied the 1945 edition of the book. [Western American Literature 43.4 (Winter 2009)]

The Oregon Trail. (Full text of the book is online here.)

Researched and written by Jane Rohman, 1988

Updated, 2010 and 2015, 2017

Benton: Art Treasures of Nebraska — Video by NET Nebraska

Benton: Art Treasures of Nebraska — Video by NET Nebraska