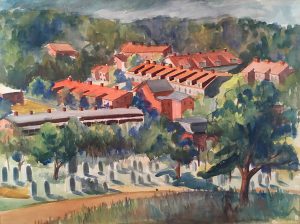

View artwork

Praised by former students as an exceptional teacher with a serious, no-nonsense approach and an unending devotion to the arts, Katherine Faulkner was born on June 23, 1901, in Syracuse, New York. Little is known about her family or her childhood. She contracted polio at a young age and was not expected to live past her teen years. She survived, however, and received her Bachelor of Arts degree in 1925 from Syracuse University. She then attended The Art Students League for two years and, in the summer of 1928, the Grand Central School of Art, both in New York City. That fall she arrived at the Art Department of the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, where she earned additional credit hours while teaching, eventually obtaining her Master of Fine Arts degree from Syracuse University through summer course work. She remained at the University of Nebraska for 20 years.

The summer of 1933 she studied in New York City under Hans Hofmann, who had arrived from Munich in 1932. A later catalyst of the abstract expressionist movement, he was reputed to be an excellent teacher of art. Clement Greenburg, the noted art critic, said of his teaching, “You could learn more about Matisse’s color from Hofmann than from Matisse himself,” and “No one in this country, then or since, understood Cubism as thoroughly as Hofmann did.”

Like Hofmann, Faulkner also was considered an exceptional teacher. Among her other teachers and role models were Boardman Robinson, cartoonist, illustrator, and founder of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center; and Henry Varnum Poor, noted for his fresco mural art. Both artists were widely influential in the mid 1920s and ‘30s. Unlike some of the women who preceded her, teaching was more than just a livelihood for Faulkner, and she was quoted as saying that an art instructor’s teaching should come before “his own creative work.” Nevertheless she pursued her own art, continued to study art, and was affiliated with several art organizations including the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, the Northwest Print Makers group, and the Lincoln Artists Guild. Between 1936 and 1940, she exhibited in more than 50 shows, according to her resume, and in 1946 she was elected to Delta Phi Delta, an honorary art organization. Her style while in Nebraska was realistic genre painting. However, some years later, in Wisconsin, she experimented with geometric forms and produced many prints.

The seriousness of her teaching gave former art students pause about their other interests. Faulkner told a student who also played baseball at the University, “You know, you’ll have to choose between being a baseball player and being an artist. You can’t do both.” She also warned him that he risked hurting his painting hand if he continued to play baseball. About a colleague who was engaged to be married, Faulkner said “biology ruins more good artists.”

In the late 1930s, Faulkner submitted work to the Treasury Department’s Section of Painting and Sculpture in Washington, D.C. to be considered for a commission project in Dallas. Although she was turned down for that project, she was selected to paint a mural for the newly built post office in Valentine, Nebraska, located in Cherry County. Of the 14 murals created in Nebraska post offices from 1938 to 1942 under the auspices of the Treasury, Faulkner was the only artist chosen who resided in the state.

In 1939 she finished End of the Trail, an oil-on-plaster depiction of a train depot where goods were arriving for the early settlers of the West. Like many artists working in small towns, Faulkner ran up against local opinions about what should be painted and how it should be done. Although Faulkner had traveled to Cherry County, sketched the landscape, and researched historical facts about the era, she was criticized for inaccuracy. Some said the treeless landscape in the background did not match up with the direction the train was heading, and that the locomotive looked like a toy. In defense, the artist explained that the mural was regional not local, and because it was interpretive it should not be necessary that it exactly conform to reality in every detail.

The mural is still on display in the post office building which, since 1980, has housed an Educational Service Unit. It can be surmised that the Valentine residents ultimately accepted it. Faulkner’s art also resides in the collections of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia; CU Art Museum, University of Colorado at Boulder; Museum of Art at Brigham Young University; Sheldon Museum of Art and Great Plains Art Collection, both in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Kady Faulkner and a colleague, Dwight Kirsch, an instructor and artist who also directed the University of Nebraska galleries, were instrumental in developing the Art Department and its relationship between the University and the Nebraska Art Association. Their enthusiasm and high expectations are said to have trickled down to their students. However, in 1947 Dr. Duard Laging was hired as head of the Department, upsetting the Department’s status quo.

Three years later, Faulkner resigned. Her resignation and cutbacks in the art program caused “public protests” from the alumni of the Art Department. In an Omaha World-Herald article, Faulkner explained her reasons for leaving, stating that she no longer trusted her superiors and that talk about democracy in the Department was not being carried out. She went on to address her concerns about the lack of discipline in the way the program was being run. She cited laboratory art classes scheduled for three hours that were being completed in 20 minutes and claimed that such practices were condoned by the Department. Five faculty members, including Dwight Kirsch, considered tendering their resignations in the wake of hers.

After leaving Nebraska, Faulkner settled in Kenosha, Wisconsin, where her grandparents, the founders of Simmons Mattress Company, had their business. She became head of the Art Department at Kemper Hall, an Episcopalian boarding school for girls, where she remained until her retirement in 1972. Her reputation as a superior educator continued in Kenosha. According to a former student, there were many artists, architects, and photographers who would name Faulkner as an important influence on their career choices.

Faulkner had long dreamed of developing an art center for Kenosha. After her death, she was named an honorary member of the Kenosha Art Association and a scholarship in her name was established by the Greater Kenosha Arts Council, an organization formed to build an art center. In 1976 the former mansion of Mr. and Mrs. James Anderson had been given to Kemper County. The Anderson Art Center was later established in the mansion, and Faulkner’s dream was fulfilled after her death in Kenosha in 1977.

Excerpt from “Nebraska Women Artists, 1850-1950“ published in Nebraska History, Volume 88, Number 3, Fall 2007, Nebraska State Historical Society.

Researched and written by Sharon L. Kennedy, 2007

Updated 2013