View artwork

The Legacy of John James Audubon

John James Audubon. The name brings to mind the majestic beauty and grace of a vast collective of wildlife portraiture. However, it is crucial to remember Audubon’s detailed scientific observations as well, for his work in that capacity is still valid today. Fascinated by the natural world around him, Audubon’s ability to capture image and word has enriched the worlds of both art and science immeasurably.

Audubon embraced a passion for exploration, and transformed himself from a French gentleman into an American wilderness man. The artist was fond of myth and legend – and he played his romanticized role as an expeditionary well. Many rumors, some perpetuated by the artist himself, aided this image. In one of these rumors, Audubon was purported to be the son of a French nobleman; in another, Audubon was the pupil of the great French master, Jacques-Louis David. Whether these attributions are fact or fiction, it remains that John James Audubon is an historical figure worthy of recognition.

John James Audubon: The Early Years

Audubon was born in Santo Domingo, now Haiti, in 1785. His father was a French sea captain and plantation owner, his mother, the captain’s mistress. Audubon’s mother died shortly after his birth, but it was several years before the boy came to reside with his father’s legal family in Nantes, France. Mrs. Audubon embraced the boy as her own, and saw that he was provided with the lifestyle of a young country gentleman. From an early age, Audubon maintained an interest in the natural world around him, and responded to it with drawn images of the flora and fauna he observed.

In 1803, when he was 18, Audubon traveled to America to avoid conscription into the Napoleonic army. There he was expected to look after his father’s investment property, the estate at Mill Grove (near Philadelphia). In fact, there was really very little overseeing to be done on the property and the young man was able to live a life of few cares and responsibilities. Through his prowess at hunting, he amassed an extensive collection of wildlife specimens, which were preserved and used for sketching. Young Audubon is credited with conducting the first known North American banding experiment, in which he discovered that the birds known as the Eastern Phoebes returned to the same nesting sites each year.

In 1805 Audubon returned to France for a year, where he perfected many bird sketches. Upon returning to America in 1806, he continued drawing and developed a specialized technique of using wire armatures within specimens, enabling him to pose birds in life-like poses. However, though very happy with his artistic pursuits, he longed to explore a career beyond the estate. In 1807 he traveled to Louisville, Kentucky to establish business connections, returning to Mill Grove the following year to marry fiancée Lucy Bakewell and whisk her to Louisville. The year 1810 must have been a pivotal point in Audubon’s life. That year the young man met ornithological illustrator Alexander Wilson, who was considered the father of American ornithology. After viewing Wilson’s work, Audubon’s business partner Ferdinand Rozier told him his drawings were better and convinced Audubon to publish his work.

The following years were punctuated with unrest for the family, which had by then grown by two sons (two daughters died). In search of business opportunities, the family relocated several times. After several business successes including general stores in Missouri and Illinois, Audubon overextended himself in an economic downturn and was distracted by his passion – painting birds instead of minding his business ventures, leading in 1819, at age 34, to his imprisonment for a period on bankruptcy charges.

The Professional Artist and The Birds of America

For a time, the Audubon family subsisted on the meager earnings that the artist made as a charcoal portraitist. Settling in Cincinnati in 1820, he worked for a time as a taxidermist. Unsatisfied with this way of life, the artist made a drastic decision. He was determined to travel the Mississippi in search of bird specimens, which he intended to introduce into a grand art and science book form. Accompanied by an assistant, a gun, art supplies, and little else, he took on the persona of a seasoned frontiersman. Gone were the days of dressing as a businessman – Audubon embraced the hardship of frontier travel and reinvented himself as a rough-hewn explorer and naturalist.

Upon reaching New Orleans, Audubon and his assistant Joseph Mason, his 12-year old pupil, tried to amass money for a great expedition. In the meantime, Audubon earned a little money to send home by doing miscellaneous artwork. Lucy was able to support the family by serving as a tutor to the gentry. In 1822 Audubon, accompanied by his sons and assistant Mason, journeyed to Natchez, Mississippi. Over the next two years, Audubon honed his style and created an impressive collection of bird drawings, for which Mason had rendered many life-like backgrounds.

In 1824 the artist traveled to Philadelphia to seek support for his grandiose bird project. However, Audubon was rejected by most of the connoisseurs he had hoped to impress. His buckskin attire, greased hair, and lack of educational credentials made them suspicious and uncomfortable. Furthermore, many were unwilling to accept Audubon’s new, lively portrayals of birdlife because they had a financial investment in the now deceased Alexander Wilson’s work, and saw Audubon’s superior drawings as an economic threat. Audubon was a shameless promoter of his own art, and his criticisms of Wilson’s uninspired and lifeless bird poses failed to endear him to those he met. Unable to find a publisher first in Philadelphia and then New York City, the artist looked to England.

Upon arriving there in 1826, Audubon was confronted by a quite different audience. The people of England and Scotland were intrigued by the looks and manner of Audubon’s frontier persona. Indeed, to them he looked like a romanticized character from a James Fenimore Cooper story. Audubon’s “frontier” birds were admired as well, and the artist began looking for an engraver to help him render saleable prints. The artist entered into an agreement with William Lizars of Edinburgh to execute the prints, but Lizars completed only ten plates before pulling away from the project.

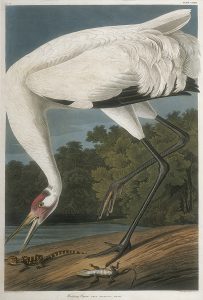

The artist pressed on, forging a business relationship with London engraver Robert Havell, Jr. The two men worked closely together to retain the artistic integrity of the prints, and were even able to improve some of the compositions. The result: The Birds of America, a series containing 435 handcolored plates of life-sized birds. The lithographs, measuring more than two by three feet each, were issued in four volumes, including a synopsis and index, between the years of 1827 and 1838. They were accompanied by a five-volume work calledOrnithological Biography, which contained Audubon’s scientific essays about each of the birds included in the project. These sets were sold by subscription at the regal price of $1,000 each, and Audubon’s tenacious marketing skills enabled him to sell more than 200 sets over the years. Audubon was now able to live comfortably and with some renown.

In 1829 the artist returned to the United States. He continued to travel and collect specimens to supplement The Birds of America, but returned to England only twice to view the production of the engravings. In 1838, the last print was issued. However, Audubon envisioned more for The Birds of America. By 1840 the artist was determined to make more copies in a smaller, more compact edition, called an octavo. Audubon contracted with Philadelphia lithographer John T. Bowen for this project. Audubon, his son John Woodhouse, and the lithographer began careful production, and the project was complete by 1845.

Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America

Audubon seems never to have tired of his artistic and scientific pursuits. In 1842 he began taking subscriptions for another exciting project, Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America. It was his desire to compile another collection – this time featuring mammalian life. The year 1843 brought yet another expedition for specimens – this time, Audubon traveled west to the upper Missouri River and to the Dakotas. In 1845 the first folio, or section, of Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America became a reality. Unfortunately, Audubon’s sight was failing. He began to show marked traits of senility and was unable to continue with the project. His son John Woodhouse continued to collect specimens and to create images for the volume, but Audubon suffered a stroke just prior to the completion of the third and final folio. John James Audubon, an American legend, passed away at his New York estate in 1851 at the age of 65.

Birds of America.

Researched and written by Kristin Gebhardt, 2004.

Updated 2010