View artwork

Chris Gryder began his exploration of art by studying architecture. A sincere and dedicated commitment to the subject led to his acquaintance with artists, methods, and concepts that later became the inspiration for his work in sculpture and clay. From the visionary designs of Antonio Gaudi and the philosophy of Louis Sullivan, to experimental work in mold-making for architectural pieces, Gryder pieced together a singular aesthetic and an uncommon process of sculpture making.

Born in Montgomery, Alabama, Gryder moved with his family to Omaha, Nebraska while in middle school. After completing his secondary education, he enrolled in Tulane University’s five-year architecture program taking him to New Orleans. During his undergraduate work, his interest in the straight, clean lines of modern and postmodern architecture was tentative. His disillusionment with Bauhaus purity became quite apparent when he discovered the work of Gaudi. His eyes were opened to a new world of architectural form. Gaudi incorporated ceramics in his architectural surfaces. Ornament was not only used, it encompassed entire buildings. It was the building. While Gaudi’s work gets categorized as Art Nouveau, it fully transcended the movement by taking the typical flowing, plantlike forms so popular at the time and using them not only as motif but as architectural framework. He was a sculptor on a very grand scale. Gryder responded to everything about the work: the diversity of form, the hands-on quality of execution, the acceptance of ornament, the abundance or references to the natural world.

For three years, Gryder worked in the field of architecture until a five-year stint in the desert of Arizona turned his head to the world of sculpture. He lived and worked on Paolo Soleri’s project, Arcosanti, which had been developing prototypes for urban ideas since the 1970s in a clay studio and bronze foundry 65 miles north of Phoenix. While Gryder worked there building architectural pieces, he overwhelmingly responded to building with his hands, a pastime used less and less in the field of architecture. Working in the ceramic studio, he gained rudimentary technical knowledge and started playing with the idea of making molds in the negative. With memories of Gaudi emerging, he began an interest in making organic sculptural forms.

Gryder began graduate work at Rhode Island School of Design with ideas and inspiration fueled by his recent explorations at Arcosanti. The most striking aspect of his art making, blossoming during his graduate years, is the atypical process he uses to create vessels. All pieces are fashioned in the negative. Explained in basic terms, he first builds a box and fills it with packed silt. With his hands and simple tools, he carves a negative into the silt, which will become the exterior of the vessel. From there he pours commercial slip (with roughly the density of a thick milk shake) into the carved cavity. The slip dries slightly over several hours until Gryder scoops out all the slip that is still liquid. When the clay has dried completely, he breaks the mold and has a completed greenware piece. The surface is then covered with neutral colors of terra sigillata.

The process is involved and time consuming, but appealing to Gryder. He explains that in a one-off single casting, the artist doesn’t have to concentrate time and energy on preparing the mold for repetitive use, a process of accommodation which often informs the piece visually. More freedom of design is allowed with a mold that dissolves after each piece. The procedure also offers the opportunity for more spontaneous and unexpected results.

Covering the outside of Gryder’s vessels are odd protruding forms that travel in patterns. When aware of the artist’s process, one can imagine the act of scooping that produces the curious structure and contour. Whether seeming to be strange botanical elements or grotesque geological formations, one is reminded somewhat of Gaudi. The surface is rough, like sand, with peculiar gatherings of hardened sediment tucked into the tight spaces between forms. Without knowing the process, a seasoned clay enthusiast would be hard-pressed to understand how the extraordinary surface was achieved.

In contrast to the swelling forms, coarse texture, and matte patina of the exterior, the inside finish is smooth and satiny, and a different color. The fervent dissimilarity of surface is entirely arresting, reminding one of a broken coconut or a sea creature with an open shell. Historically, vessels have represented, among other things, the human soul. Gryder’s pieces allude to this symbolism with their harsh, seemingly protective outer layer which opens to reveal a velvety interior.

Vessels were Gryder’s primary focus in graduate school, but he also dabbled in tiles using the same process. After graduating and finding a following for his work, tiles became more of a focus, and eventually their popularity and his interest in them pushed them to the forefront of his production.

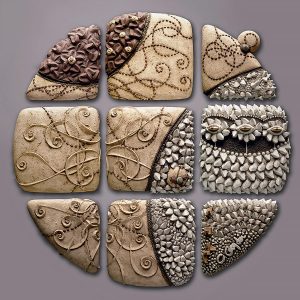

Like the exterior of the vessels, Gryder’s tile surfaces have a sandstone-like quality. The aesthetic of Gryder’s tiles unite his former training and influences in modern design with his passion for the sensual and primordial. Furthermore, the two-dimensional aspect of tiles leaves room for more pictorial and narrative exploration. The tiles as a group manifest themselves in large wall-relief constructions, often –10 feet in length. Gryder starts by developing the piece linearly, focusing on overall form. The divisions of space could represent primitive ceremonial diagrams, molecular models, or planetary trajectories, conjuring associations with the metaphysical and the scientific. Possible horizons divide night and day, sea and land, earth and sky, above ground and underground. The divisions seem proportional and balanced enough to give the impression that the artist has used the Golden Mean for calculation. Indeed, a sense of the mathematical pervades the work, and is all the more emphasized by the grid formation of the tiles themselves. Like crop circles in a field of perfectly straight rows of corn, one wonders if an indecipherable map has been laid out, its function hidden behind its mysterious beauty.

Within the individual tiles are myriad abstract forms which reference, for the most part, the natural world. At first one is confident in deciphering leaf forms, but on closer examination leaves could be feathers, wings, or crystalline growth. A suggestion of insects, fruits, seeds, and pods seems feasible. The eye can follow forms that insinuate ocean waves, branches on a tree, animal trails, veins on a leaf, or water ripples. The rises in the relief hint at a possible model of a landscape. And while features of the natural world are hinted at, it wouldn’t be far-fetched to see the spinning cogs and mechanisms of a moving contraption. The whole impression is one of liveliness and action.

Many of Gryder’s influences reach far back into history, probably due to the proliferation of ornamental carved relief in primitive cultures. The artist’s design arrangements and motifs recall Pre-Columbian architectural facades, especially Incan patterns and Mayan imagery. As in prehistoric cultures, he frequently uses circular forms with layers radiating from a center like icons or mandalas. Added to these influences of design is the fact that the art of early cultures now exhibits the damage of time. Gryder’s technique lends a quality of aged or decayed stone, reminiscent of ancient ruins.

The success of Chris Gryder’s work lies in his ability to combine and integrate so many opposing approaches to expression. With a seamless style, he manages to mix the purity of modernism with a joyous celebration of profuse ornament, an ostensibly impossible task. His imagery invokes disparate ideas, from the analytical approach of science to the spiritual demonstrations of primitive culture. The work captures a feeling of the ancient and the new, the naïve and the sophisticated, spontaneity and order. Gryder’s skill in encompassing and uniting divergent themes offers the viewer an exceptionally rich experience.

Excerpt from Ceramics Monthly magazine, November 2006

“Negative Impact: Chris Gryder’s Silt Castings” By Dori DeCamillis

Posted, 2013